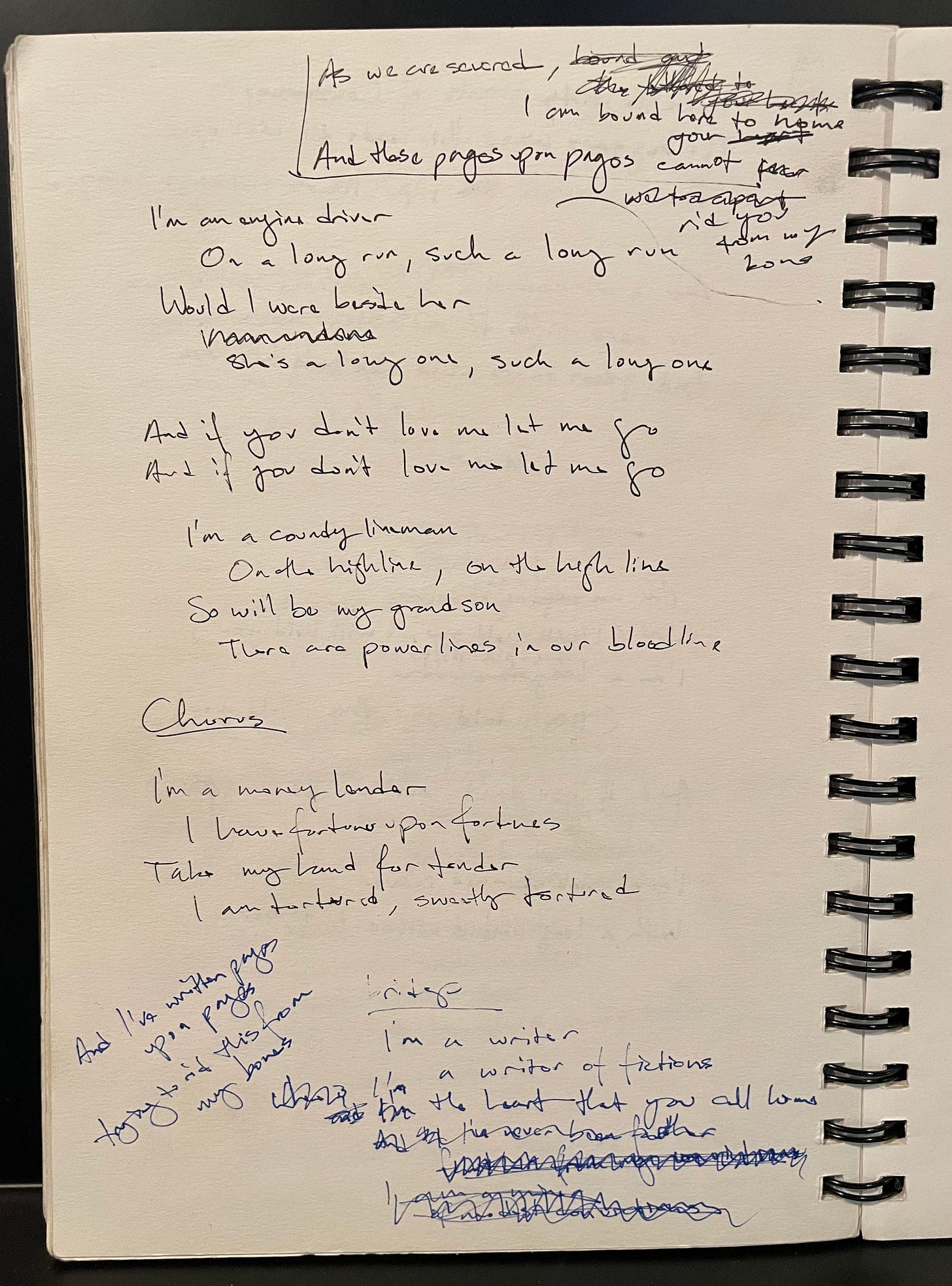

THE ENGINE DRIVER1

I’m an engine driver2

On a long run, on a long run

Would I were beside her

She’s a long one, such a long one

And if you don’t love me let me go3

And if you don’t love me let me go

I’m a county lineman4

On the Hi-Line5, on the Hi-Line

So will be my grandson

There are power lines in our bloodlines6

And if you don’t love me let me go

And if you don’t love me let me go7

And I am a writer, writer of fictions8

I am the heart that you call home

And I’ve written pages upon pages

Trying to rid you from my bones

My bones9

I’m a moneylender10

I have fortunes upon fortunes

Take my hand for tender

I am tortured, ever tortured11

And if you don’t love me let me go

And if you don’t love me let me go

And I am a writer, writer of fictions

I am the heart that you call home

And I’ve written pages upon pages

Trying to rid you from my bones

I am a writer, writer of fictions

I am all that you call home

And I’ve written pages upon pages

Trying to rid you from my bones

My bones

And if you don’t love me let me go

And if you don’t love me let me go12

This song was written in 2004, in NE Portland, in a room overlooking NE Fargo street. Carson and I lived in that house for a few years; we rented it from Chad Crouch, the owner and operator of Hush Records. The Thermals practiced in the basement. I wrote this song on a twelve-string guitar, a Martin dreadnought twelve-string that I’ve since sold, and it’s always been a twelve-string song. The driver (ha ha) behind the song is those verse chords — Cmaj7 > Em > Bm > Cmaj7 > G > D — and the lyric and melody grew out of those chords. I always thought the chords had an interesting weave to them — the part that you might call the bridge or the pre-chorus (“And if you don’t love me let me go”) effectively inverts the pattern of the verse chords, going Cmaj7 > G > D > Cmaj7 > Em > Bm. It’s a neat trick and it gives a nice feel to the pre-chorus that sets it apart from the verse, but to this day, it has occasion to trip us all up.

Why an engine driver? And what is an engine driver? I’m sure this engine driver is somehow related (second cousins?) to Ivor from The Who’s “A Quick One While He’s Away” — that song was an inspiration to me in those days and, in my mind, is the model for a lot of the wild and wooly multi-suite songs we did then. It is the gold standard for all tongue-in-cheek, don’t-give-a-fuck rock ‘n’ roll symphonies. “The Engine Driver” also slotted in my mind as another one of my Occupational Biographies, and our engine driver was taking his place alongside the architect and the soldier, the Spaniard and the chimbley sweep, the legionnaire and the Chinese trapeze artist. For a while, it was an interesting way for me to find my way into a song, a way to define clearly from the outset who was singing, or what this voice was singing about. To my mind, it was always following in the grand tradition of Lou Reed’s “…Says” songs (Lisa, Caroline, Candy, Stephanie, Sister Ray — they all have something to say). These people — these occupations — all feel of the same piece, existing in the same universe. Their job is the basic describer that gets you in the door, and then you can hear the rest of their story. He’s an engine driver; I’m sure he’s got some tales to tell.

Here’s that pre-chorus I was talking about, the one that is sung over an inversion of the verse chords. I don’t know where these lines came from — I think they were just drawn out of the chords, the melody, and the forward momentum of the song. I didn’t labor them, they were just there. I think the thing that makes these lines work is that the word “love” is sung on the first hint of the chord progression inversion: It arrives on a G major; if it was sung over the verse chords, that chord would be an E minor, the relative minor of G. Two very different feels there. So you have some lift on the word “love,” and I think that makes it really sing. Is this too much inside baseball?

Here we have a new voice, a new occupation. And another callout to another foundational song: “The Wichita Lineman,” written by Jimmy Webb, made famous by Glen Campbell. Like most people, I knew this song growing up, but in a peripheral way — it was just a song that occasionally popped up on AM radio. It wasn’t until I was in my twenties, when I was really starting to write songs, that I dug into the song and learned its mysteries. Talk about a puzzle of a chord progression — that “Searching in the sun for another overload” line and the chords that underpin it still kill me; it’s so unexpected and yet fits so well. I felt like my engine driver shared some connection to Webb’s lineman — both are effectively solitary jobs, lonely by their very nature. So I put a lineman in the song, another aspect of the loneliness of the engine driver.

The Hi-Line is the northern-most run of railroad in Montana — the northern-most railroad line in the lower 48, as a matter of fact. It runs from Havre to Whitefish. It also serves as a name for that entire region, all the small towns and communities the line connected, or that have, over time, grown up around it. The Hi-Line is some of the most incredible country you’ll ever see. It is massive granite mountains and wide open plains. It is also some of the most desolate and lonely country in the world. The idea of the Hi-Line, and the people who live in it and grew up in it, has been a source of fascination for me since I was a kid. It has a kind of mythical status, both because of its beauty and its desolation. What better place to put our lineman than on the Hi-Line? Loneliness is in his bones.

I met a Montanan lineman in college, a friend of a friend. He didn’t work on the Hi-Line; he was stationed mainly around Butte. I remember him telling me stories about working the power lines, servicing poles and towers in the middle of nowhere. I’m sure it was thankless work, but he seemed pleased. He was a typical Montanan, smitten by his home state, and he loved being out in the prairies and woods and backroads. To my mind, this sentiment, this being fated to working the electrical lines, seemed both a romantic idea and a kind of curse.

Random thought: I remember teaching this song to the band and rehearsing it in the basement of Rachel Blumberg’s house — she was our drummer at the time. Our guitar player, Chris Funk, was in the middle of a nasty breakup, one of those ones that never seem to end, and I remember him repeating that line, “If you don’t love me let me go,” at a rehearsal, in a kind of wistful way. The line didn’t feel like it belonged to anyone else at that point, it was still new and fresh and just some words in a song. But when he connected with the phrase, it struck me there was something universal there, something everyone could latch on to for one reason or another.

In typical fashion, the chorus centers around the dominant major chord of the scale, that wide-open G. This is a new voice, a new first person pronoun — my own voice, I suppose. The writer. For whom the lineman and the engine driver (and, eventually, the moneylender) are all aspects. He’s a writer of fiction(s). Made up stuff. I’d only just quit my day job at a bookstore and was finally reckoning with this thing I was doing, writing songs and playing in a band. I think I was reflecting on the inherent loneliness of my own, very new job. I don’t think I’d ever really considered how much of the real work of musicianship and songwriting was done in solitude. There’s a thread to be drawn between songwriters and engine drivers and linemen — that sweet sort of melancholy.

Again with the bones. Bones this, bones that. I have no explanation; I like bones.

This remains a bit of a mystery to me, this moneylender. I think a lot of my songwriting — particularly at this time — was not labored over very much, and often the first idea that made its way on to the page was the thing that stuck. This moneylender feels a bit out of step with the rest of the characters in the song, and doesn’t quite have the romance of the lonely steamtrain driver or the Hi-Line lineman, but I imagine that’s what initially appealed to me. I wanted something a little less picturesque and something more… I dunno… picaresque. I mean, it makes sense, it follows: Moneylending, I imagine, is also a solitary job, inherently lonely. Isolated.

This line was initially “I am tortured, sweetly tortured.” I changed the “sweetly” to “ever” somewhere between the writing of the song and the recording of it. I remember thinking that I was relying on “sweet” as a descriptor a little too often and wanted to change it up. In retrospect, I might’ve kept it. I played this song on my first solo tour, before we recorded Picaresque, and the moneylender’s torture, then, was of the sweetly sort. After the record came out, someone came up to me after the show and told me they were bummed I’d changed it to “ever tortured.” Alas! You can’t please them all…

According to setlist.fm, we’ve played this song live 248 times. Huh. This is the first time that I’ve reckoned with that statistic. That’s a lot of times. And yet: I’m not sick of it. You might be, but I’m not — not so far. I always seem to find something new in it. And looking out into the crowd and watching a sea of faces sing that pre-chorus is never not moving. It feels like a real shared moment, that thing that transcends music and just puts us all into each others’ spaces, letting us all feel something real together for a moment. That kind of shared loneliness.

Engine Driver, Wichita Lineman, and Fisherman’s Blues by The Waterboys are all invariably linked to me like they are just a complementary trio in my mind forever. I do love the occupational biography songs!

I lived in Havre for a few years, and traveled along the hi line for work. It definitely imprints upon you quickly.

You have to buy into the magic of the region or else the desolation will overtake you. It definitely wasn't for everybody. The -50 temps didn't help either.