The Reading Room, April 29, 2023

Books read:

The Metamorphosis and Other Stories, Franz Kafka

The All Of It, Jeanette Halen

Foster, Claire Keegan

Brave New World, Aldous Huxley

Books reading:

Barnaby Rudge, Charles Dickens

A Children’s Bible, Lydia Millet

Steering the Craft, Ursula K. LeGuin

I wanted to begin this month’s edition of The Reading Room with a short meditation about the word Kafkaesque. Full disclosure: until maybe four years ago, my understanding of what Kafkaesque meant, and things being Kafkaesque, was limited to, I think, most peoples’ understanding of the word, which is to say it is a word somewhat divorced from its origin. When we say something is Kafkaesque, I think, we mean that something is byzantine or overly convoluted. We think of elaborate bureaucracies and systems that are designed to confuse and confound. We think of a man, perhaps, in a black suit, wearing a hat, and walking through some gray maze of corridors.

Even though I had read a little bit of Kafka in college — and by little I mean, to the best of my recollection, I had read the short story “The Metamorphosis” and part of the The Trial for some 20th century lit class — it was the general understanding of the word Kafkaesque that informed what that word meant or what it described. The movie Brazil is Kafkaesque. The experience of navigating the American health care system is Kafkaesque. Both of these things are true, but they tend to oversimplify Kafka’s whole, you know, deal.

Three years ago, on a search for a new book to read, I was stumbling through the K section of some book store or another and realized that I had read precious little of Kafka’s work, despite having enough supposed knowledge of his general vibe as to use the word Kafkaesque to describe various Kafkaesque things. It was time to remedy that! Randomly, my first return to the famous Czech weirdo was by way of an audiobook of The Castle, read by Geoffrey Howard. Imagine my surprise to discover that the world of Kafka (and thereby things that are truly Kafkaesque) is soooo much more wide and wild and nuanced than anything I’d ever described as being Kafkaesque. Shame on me! For one thing, Kafka is funny. That’s the thing that we miss — or at least I’d missed — by imagining that poor hapless black-suited guy in that labyrinth of gray corridors. The idea tends to be humorless. Kafka’s writing, in actuality, is, like, knee-slapping, low-brow, Laurel and Hardy funny. From there, I was determined to make my way through the rest of his work; this is still an ongoing project. I read The Trial last year; I just finished his collection of short stories and novellas in the Penguin volume The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. I’m currently dipping in and out of the recent translation of his diaries.

I feel I now have a different conception of what Kafkaesque means. Along with the sometimes-forgotten comedy of his work, the word, to me, suggests things that are, above all, dream-like. And not dream-like in the sense that it is particularly hazy or half-remembered, or wondrous and magical — but that real quality of dream-experience. The conversation with someone that goes on a little bit too long and becomes too granular, too personal. A sudden diversion from an activity, one that leads you farther and farther away from your goal, until it’s too late to return. Things that are darkly humorous; the comedy in hopeless tasks that are forever being confounded by the people around you. Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Unconsoled is deeply, unabashedly Kafkaesque. It’s more Kafkaesque than anything Kafka might’ve written.

All this was on my mind as I finished The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. The title story is a stone-cold classic, of course, though I’d forgotten how seriously comic it is. It’s not just weird-weird, it’s funny-weird. And the turn at the end, how the family forgets about Gregor altogether and the story pivots to a kind of celebration of the sister’s thriving — it’s all so sad; so sad and funny. Poor Gregor. I really loved “The Stoker” as well — it perhaps was the most dream-like of them all.

Kafka, an incurable insomniac, was known to write in the wee hours of the night as a way to harness that liminal space between waking and dreaming. And that, I think, is what most colors his work and makes it captivating and novel. So the next time someone tells you their trip to the DMV was positively Kafkaesque, you should ask, “It was dream-like and subversively comical?”

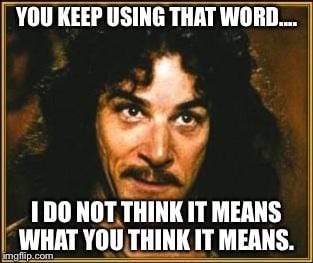

I had a few days in Astoria to myself recently and I packed a handful of books to bring along with me, two of them being these slim novellas The All Of It by Jeanette Halen and Foster by Claire Keegan. My mom gave them to me. I read them both over the course of my days in Astoria. They are two peas in a pod, these two books: they both take place in Ireland and they are both slim, taut little stories. The All Of It was originally published in 1986; it’s been reissued now after my sister, Maile, gave a copy to Anne Patchett. Seriously — it’s in the foreward. Foster was published a few years ago; it was recently made into the movie The Quiet Girl. I liked both of these books quite a lot.

The All Of It is told from the perspective of a priest in rural Ireland as he fishes for salmon in a rain-swollen stream. His mind keeps going back to a conversation he had with a woman in his parish after the death of her husband. Turns out, the dead man wasn’t really her husband. I won’t spoil it for you; it’s a fantastic story with a lot of humanity in it.

Foster is about a girl who spends a summer at her relations in, again, rural Ireland. There’s a real poetry to this one; it’s such a simple and well-told story, it gets down into your bones. I couldn’t tell, at the end, if I’d read a ghost story or not — perhaps, in some way, all good stories are ghost stories in one way or another.

The lovely thing about these two books is that you can read them in an afternoon, and it was a real delight to spend time (however briefly) lost in the (rural, Irish) worlds of their pages over the course of a few days. I’ve left both copies of the books at our house in Astoria, which is often inhabited by visiting friends needing a weekend away from their homelives — a perfect environment to pick up an unknown book and finish it before it’s time to leave.

I’m currently working on a writing project that dabbles in dystopian fiction, so I’ve been taking in the leading lights of the genre over the past couple years. Jon Raymond’s Denial and Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry For the Future have found their way into The Reading Room in past episodes; I reread Orwell’s 1984 a couple years ago. I’d skipped Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World up to this point and figured now was as good a time as any. It’s wild that this is a book that was published in 1932; I’m surprised it didn’t run more afoul of censors. Huxley’s treatment of sexuality in his speculative future Britain is pretty radical — monogamy among sexual partners is frowned upon and children are encouraged to engage in “erotic play.” According to the Internet™, the book does have a history of being censored or banned, but mostly within the last thirty years (!). As far as I can tell, the only instance of it being banned during its initial publication was in Ireland. Joyce’s Ulysses, which only predates Brave New World by a decade, was famously put on trial for obscenity; Huxley’s book seems to have, at first, skated by the morality police. Maybe because it was genre fiction, and thus seemed harmless? Who knows.

In any case, it’s a fascinating book and in some ways prophetic — the pervasive taking of the panacea “soma” drug aptly predicts the current climate of pill-popping our cares away. In other ways, like most speculative fiction past its due date, it misses its mark a bit. In the afterward (“Brave New World Revisited”), Huxley does a lot of hand-wringing about Communism and how the imperial arm of the Soviet Union was ushering in the society of Brave New World faster than even he had anticipated. (The essay was written in 1958, during the height of the red scare). Huxley did not live to see the spectacular collapse of the USSR. In the wake of that, Brave New World feels a little less prescient than maybe he believed it to be.

Currently, there is a small stack of books on my bedside table: Steering the Craft, Ursula LeGuin’s slim masterclass on writing and Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible — and, as always, I am diving, intermittently, into Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge. But more on those next time. How about you? What literary soma are you currently housing by the bottlefull?

Sam and Gollum have just debated taters. I’m going to start Blood Meridian soon.

Finished 100 Years of Solitude a few weeks back. One of those books that I've always meant to read but haven't. So many words compete in my head to describe it... so I'll stick with generational. But also depressing. And beautiful. And I straight up love the magical (should I say magical realist?) elements of it. Currently reading Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel, which I'm absolutely loving, and Gideon the Ninth. Putting Kafka now on my very very long "to read" list, as well as Foster and The All of It. Excellent work making me want to read the books you recommend, Colin!