The Lion and the Cobra

Remembering Sinéad O'Connor

I didn’t know how to pronounce her name. I called her SIN-eed. She wasn’t played on the radio and I wasn’t savvy to the few MTV late-night programs that actually broadcasted her videos, so there was no authoritative voice to correct me. I found out about her the way I did a lot of music then, from my mom’s subscription to Rolling Stone. In a January 1988 issue, Anthony DeCurtis gave her debut record four stars and said it came on “like a banshee wail across the bogs.”

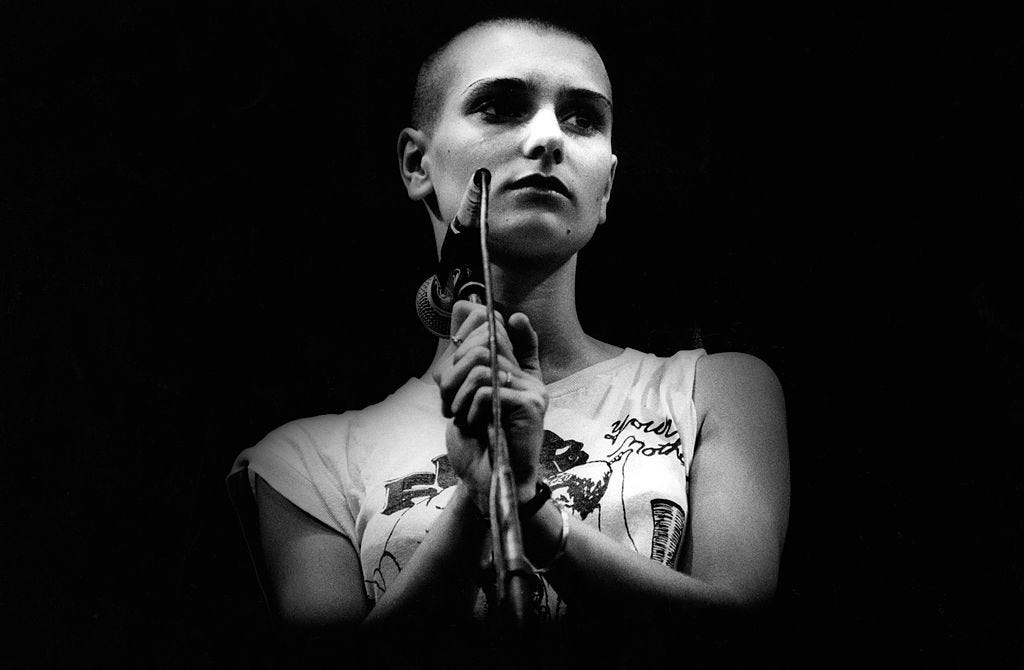

I was twelve. I was in 7th grade. Looking back, 1987 and 1988 were years where I was in the process of shedding the skin of my old tape collection, moving away from my stacks of Depeche Mode tapes, my brief dallies with Robert Palmer and Duran Duran. I was looking for music that was stranger and more off-kilter than anything they played on local radio; I was looking for music, I think, that scared me a little. Look at that cover: this bleached-photo of a shaved-bald woman, her teeth bared and her head reared back as if she were about to strike. It looked alarming; it looked a little scary. I took whatever money I had from shoveling snowy walks, caught a ride to Pegasus Music at the Capitol Hill Mall and found a copy of Sinéad O’Connor’s The Lion and the Cobra.

The cover of my cassette was different, though, than the cover the rest of the world got. On my cover, Sinéad was more introspective, her gaze looking down. But the grip of her hands on the fabric of her shirt and that skin-bald head: it was a version of femininity I had never seen before. And when I played it on my Walkman and the first breath of the first song kicks in, I think it may have been one of those moments where things just crack open and some kind of seam is made, one that will change you forever.

Jackie left on a cold dark night

Telling me he’d be home

Sailed the seas for a hundred years

Leaving me all alone

And I’ve been dead for twenty years

I’ve been washing the sand

With my ghostly tears

Searching the shores for my Jackie-o

That’s the first two verses, right out of the gate. A guitar line starts up this urgent rhythm beneath her whisper-quiet voice; twice through the progression, and it’s all you need to know: a woman is telling the story of her missing sailor husband and she’s dead. I think it’s that line “I’ve been dead for twenty years” that’s told in the sort of off-handed way only a ghost would use to describe herself, I think that is the line that hit home for me. Being dead is nothing; it’s the missing of her Jackie-o that is everything.

When I learned, yesterday, that Sinéad had died at 56, I immediately put on The Lion and the Cobra and was so moved, hearing this song again. How brave was this, in 1987, when pop lyric-writing was meant to be about more earth-bound passions (“So slide over here / And give me a moment / Your moves are so raw / I’ve got to let you know / You’re one of my kind”) or else muddled and veiled by poesy (“Sleight of hand and twist of fate / In a bed of nails she makes me wait / And I wait without you”) — how brave to have the first sung lines of your debut record be the setup for a goddamn ghost story. This song made such a lasting impression on me, such a chord was struck. Its DNA is in everything I write even now, thirty five years later.

I played that tape thin over the next few years; learned it so inside and out that the ghost of the next song lived in the spaces between the tracks. The chords in “Mandinka” were some of the first I ever learned on guitar, though I could only ever do the verse, not the chorus. Nearly blew my mom’s speakers out, I’m sure, listening to “Troy” at a hair-raising level, forgetting that the volume swell when that string part kicks in is, like, fifteen db higher than the rest of the song. “Don’t Call Me Joe,” via DeCurtis’s RS review, introduced me to both Velvet Underground and The Jesus and Mary Chain — after falling in love with the song, I had to seek out its progenitors.

I think by the time her second album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, came out, I’d moved on to other bands, to other records. It didn’t grab me like her first record did. Over the years, I’ve come back to her music — Universal Mother is another great one — but it couldn’t match the connection I’d had with The Lion and the Cobra. I did not lose my love and admiration for her, though, as a singer, a performer, and a songwriter.

I never met her in person, but that’s okay. By all accounts, she could be a prickly hang. The closest I ever got was in 2009, on a European tour, when our bus was parked up in Dover, waiting to board the Channel Tunnel train. There was another bus in the lot, one that was heading in the opposite direction, and it turned out to be Sinéad’s bus. Our tour manager had been on a tour with her a few years prior and she popped over to say hello. I didn’t join her — I think I didn’t want to impose. It was late; I was tired. I figured there’d be other chances to say hello to a childhood hero. Alas.

So thank you, Sinéad, for everything you brought, for everything you sang and wrote. For all that you did for my evolving sense of myself and music. You were a giant. The world is better for having known you.

I was waiting for your write up.

This record and her talent is, of course, unmatched. But her ruthless bravery in speaking truth to power is what will always hit me....I think her "career killing" moment in SNL shaped who I am as a person more than anything else. And it did destroy her in a lot of ways, to continue to speak truth to power, but she never stopped. I have some experience with the consequences of refusal to stay silent in the face of abuse. But I don't ever plan on getting quiet, and I owe a lot of that to her.

I too almost blew out a few pairs speakers on Troy, as well as my then untrained voice trying to hit the high notes. Worth it. This one hit me hard.

FYI, Joshua Ray Walker's new album has a cover of Nothing Compares. He WRECKED Lizzo's "Cuz I Luv You" (in the best way) with the lead single, so it should destroy.