Big Star, Kanga Roo

From Third/Sister Lovers, 1978

3:47

Big Star’s “Kanga Roo” is one of my favorite songs of all time, and not just because of the sonic quality of the recording, or the melody, or the lyric — or the vibe, man — all these things certainly play into the all-out mastery of this song, but the thing that has always grabbed me about “Kanga Roo” — that has mystified me so completely since I first heard it — is that goddamn cowbell.

But before we get into that, let’s listen.

I’m going to ask you to listen to this song, once, all the way through. You should do this using headphones, or sitting in front of good speakers. Please do not listen through your laptop speakers or, God forbid, your phone speaker. This is an exercise in mindful listening, something that doesn’t happen very much these days. Ideally you’re in a quiet spot, you’re sitting directly in front of your speaker or you have your headphones on, you’re comfortable, your mind is clear.

Ready to listen?

Okay, press play. Listen to all three minutes and forty seven seconds. When you’re done, come back here.

How was that?

The experience for me is all at once delightful, heartbreaking, and somewhat off-putting. But before we dive into anything, we should establish some formal parameters here. To my mind, there are three things in a song: there is the general melody or lyric, which is both the melodic line that the singer is singing and what they are singing about; there is the instrumental base, which includes chord progression, key, tempo, and rhythm; and then there is the sonic quality of the thing, how it’s recorded. These three things could be broken down farther, into smaller iterations, each of them as important as the last, but for a basic sort of listener appreciation purpose, I think these three broad strokes work fine.

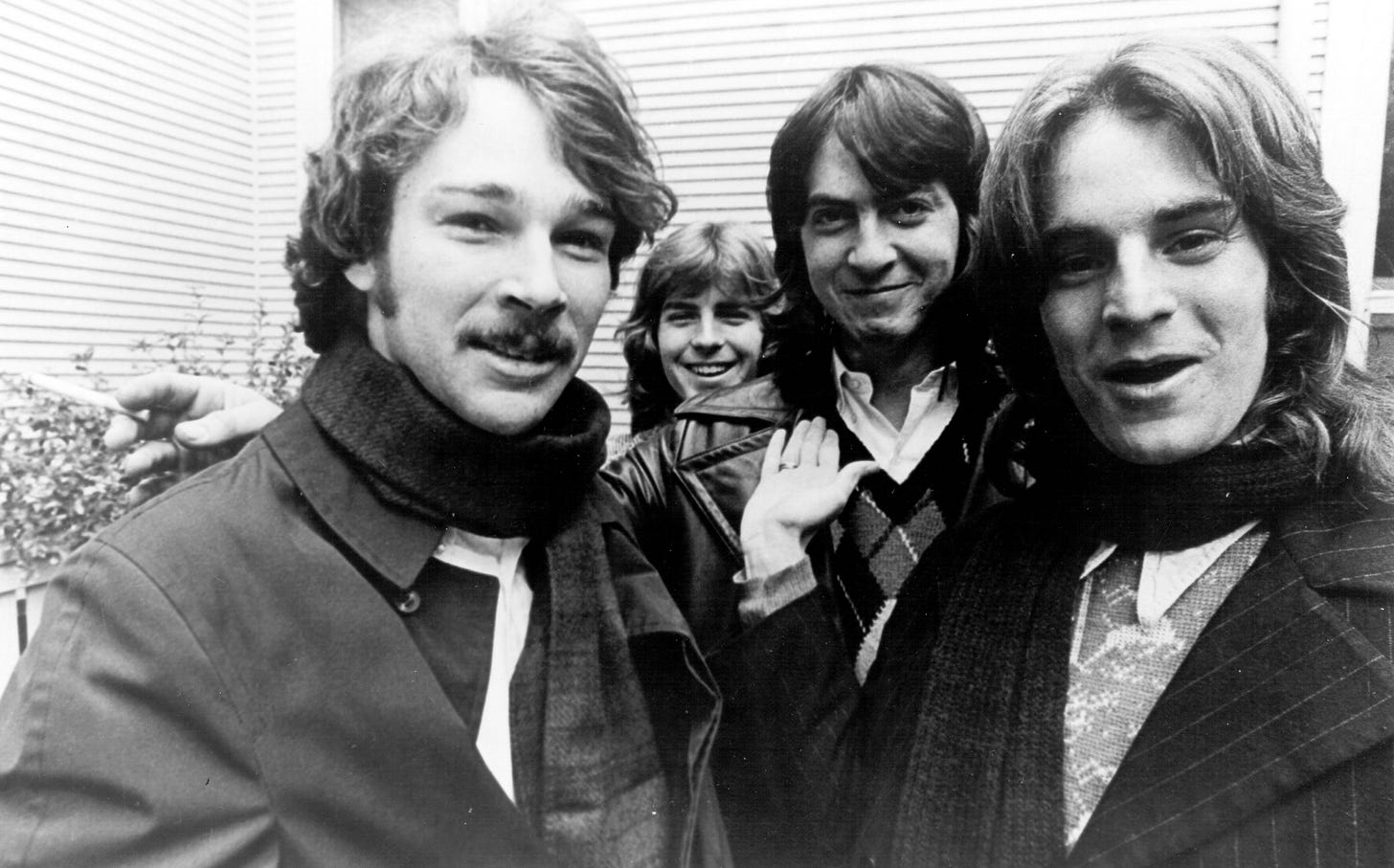

Let’s first talk about the last thing, since I think that’s one of the more important and affecting qualities of the song, if not the most important — the sonic color of the song. I’ve read that this song was recorded in the very late hours by Alex Chilton, and I’d first like to stop and say: Can’t you just hear that? If ever there was the sound of late, late night — we’re talking on the cusp of morning, it’s so late — if ever there was that sound captured on tape, then it is the sound of “Kanga Roo” by Big Star. This is not a two in the afternoon song; this is a late, late song. Alex Chilton has returned to the studio, very late, with his girlfriend at the time, Lesa Aldridge, a woman who happens to be the sister of drummer Jody Stephen’s girlfriend, which will become a working title of the record, Sister Lovers, and Alex is there with Lesa and a twelve-string guitar and he records this song, “Kanga Roo.”

According to the track logs — I have a facsimile of the originals, from the 2011 Test Pressing reissue of the record — Alex’s guitar and vocal went down on one track — meaning that both the guitar mic and the vocal mic were recorded on a single track. They are inextricable. You can actually hear the raw original track here, listed as its working title "Like St. Joan (Kanga Roo), from the 2016 Complete Third reissue (yes, it’s ridiculous — according to Discogs.com, over 40 different versions of this record have been released). I’d encourage you to do that now, just so you can hear this thing before Jim Dickinson got to it, the way it was for Alex and Lesa, that very late night.

The central focus of the song is the twelve-string guitar, and to my ear it sounds like it’s been tuned down to a “drop D” — the bottom string, typically tuned to E, has been lowered a full step to D. This is a lovely tuning; I use it all the time. There’s a richness to that bottom note tuned down, it gives such a nice droning resonance when you play a D chord. The initial idea, the experiment, of Hazards of Love, the Decemberists record from 2008, was actually to record an entire album in drop D tuning, with each song being in the key of D. (This didn’t work out quite to plan — the record modulates a bit — but that was the original idea). Putting a twelve-string guitar into drop D is a bit more of a hassle, since you’re detuning two strings instead of just one — and those twelve-string strings are awfully persnickety — but Alex felt it, and so here it is.

Okay, get ready to hit play again. Let’s take the rest of the instrumentation as it comes, and the lyric Going forward, the numbers in bold are where you should pause the track, to the best of your abilities.

Okay, play.

0:04 Sorry if that was abrupt; this will not be a smooth re-listen. We’re going to take this thing bit by bit. So here we kick off with a squeal of feedback. Right away, we get a kind of statement of purpose, here. I’ve read that the late, great Jim Dickinson, the record’s producer, overdubbed all of the instruments you hear on this song himself. Meaning: He played all of the instruments — the drums, the bass, the Mellotron (which is an early electronic keyboard — those “strings” you hear, that’s the Mellotron), and electric guitar — recording them separately, on top of the existing track of the 12 string guitar and the vocal. That’s the space that he claimed, he said. The space between the notes, he said.

My understanding is that Jim came into the studio the morning after Alex’s late night session with Lesa, and Alex played him the track, just the guitar and vocal. When Jim asked what he should do with it now, Alex reportedly said, “Well, why don’t you produce it, Mr. Producer.” A glove thrown, a challenge made. Jim gamely took Alex’s arrangement as a blueprint for the way forward. He understood the loping casualness of the song and so he muddled all over it. The feedback is Jim’s, and it sets up the tone of the song, its modus operandi. It tells us that this is a song that is, above all, about abrasiveness, about the play between soft and rough.

0:24 Let’s consider that intro, the first handful of bars before the lyrics come in. What a cosmos! Everything richly drenched in reverb — the sound of the tracks bouncing off the implacable walls of Ardent Studio’s subterranean echo chambers — with that squall of fuzzy electric guitar behind the somewhat errant, sloppy strumming on the twelve-string guitar and the weird, kind of phasey whole note of the vocal. The chord progression is a wide-open alternation between the 1 chord and the 4 chord (in this case a D chord and a G chord) — but this isn’t a music lesson, so better question: What does it feel like? It feels luscious, epic, melancholy. It feels slovenly, weird, abrasive. Good stuff.

1:10 Okay, so we have a first verse. Here it is:

I first saw you

You had on blue jeans

Your eyes couldn’t hide anything

I saw you breathing

And I saw you staring out in space

It starts out pretty banal, I’d say, with those first two lines. I first saw you, you had on blue jeans. Just a simple observation. But then it gets a little, let’s say, distracted as it goes forward — your eyes couldn’t hide anything. I saw you breathing.

I saw you breathing. Seeing it written out doesn’t underscore the importance of the line; in the song, it’s buffered by the melody and the chord progression, the sonic blanket it’s lying on, that falsetto note Chilton hits on those middle two words. I saw you breathing. It’s a new level of intimacy, a detail that the songwriter is placing into this first observation, and it’s something so abstract, it makes you question the banality of those first lines. I mean, how do you see someone breathing? How is that remarkable? Everyone is always breathing, all the time. It reminds me of a line in R.E.M.’s “You Are The Everything”: And you’re drifting off to sleep / With your teeth in your mouth. It’s a totally banal observation suddenly given this powerful weight in the context of a song — it’s because of love, because of infatuation that these everyday human conditions — breathing, having teeth — suddenly become extraordinary.

And then the verse takes flight — And I saw you moving out in space. We have entered into orbit; we have launched. We are unmoored. That electric guitar in the background, played with some kind of slide, ascends, and we have left gravity’s pull. There’s also something cliff-like, something precipitous about this line, too, because it’s a feint, it has the melody and cadence and meter from the first line of the verse, yet nothing comes after it. It sets up a second verse but just leaves us, the listener, floating in space.

Keep listening.

1:55 The drums have arrived. Again: Jim Dickinson. They’re tracked over the extant twelve-string guitar and vocals, which are blithely following their own tempo. Chilton clearly did not record his guitar and vocal to a click track — a kind of electronic metronome piped into musicians’ headphones to keep them at a steady tempo. You don’t fire up a click track when you’re wasted at the studio with your girlfriend, just wanting to create something.

So Jim Dickinson is working a bit blind here — but that’s okay, messiness is part of the game. And so the drums are wild and expressive and experiencing some kind of phase effect. You can hear it really ring out on that crash cymbal at 1:32. There’s something kind of shimmery about those high frequencies on the cymbals. According to the track log, there are a total of five tracks devoted to drums, three basic tracks and two overdubs. The basic tracks are listed as KICK, meaning a mic on the kick drum, and then just DR & DR — so I’m assuming those are two overhead mics, capturing the snare, the toms, and the cymbals. When your record drums that way, with only three mics, you’re going to get some odd results. But it gives the drums a lovely unearthly feel, and we’re here for that.

And here we’re acquainted with the second verse:

I next saw you

It was at the party

Thought you was a queen

Oh, so flirty

I came against

The voice, the protagonist, I guess you’d call him/her/them — the I of the song — they’ve come down to earth a bit here. They have descended from their launch into space. We’re now at this party, where the subject of the singer’s desire is observed again — she’s a queen, she’s flirty — and we’re now back in corporeal space and the singer is moved, and mostly by sensations a bit below the belt. I came against — it’s a sentence fragment, it doesn’t go anywhere. It’s an interruption — with a sexual suggestion in came — but it’s got that same melody as the I saw you breathing in the first verse, so we’re already primed to feel movement in this line, to get launched with it — and there’s the slide guitar again, hastening our re-ascent into the third verse, which follows a little closer upon its predecessor than the second did the first. We don’t have the bit of breathing space we were given before, a chance to come back down to earth. No, we’ll stay airborne for the third verse.

2:24 A word about that electric guitar work in the background. This was recorded in the fall of 1974, in Memphis, Tennessee. In a studio that was better known for its work with R&B artists like Isaac Hayes and Booker T and the MGs. This was two years before the Sex Pistols detonated, eleven years before The Jesus and Mary Chain let loose their squalling feedback on the world — it was a time when this kind of noise was still pretty fucking fringey and weird. And keep in mind that Jim Dickinson was a musician more accustomed to backing up Sam & Dave and Aretha Franklin, playing chords and lines that melded easily into the background, not to distract from the focus of the song, which was almost always the singer — and here he is spitting feedback from a guitar amplifier all over this ambling, rambling twelve-string acoustic guitar track. My guess is that they were both, Jim and Alex, under the influence of the Velvet Underground, a band that had, for all intents and purposes, fizzled out only a few years prior. There’s a fine version of the Velvets’ “Femme Fatale” on Third/Sister Lovers, so I’m guessing that that weird art-rock band from New York was very much in the air during these sessions.

But here we are back to the verse, to our protagonist, this partygoer, this astronaut:

Didn’t say excuse

Knew what I was doing

We looked very fine

As we were leaving

They’re awfully fragmented, these lines, but you get the idea. Lyrics, particularly of the rock persuasion, have a nice elasticity to them. Hip-fire is welcome; never mind correct grammar. There’s a lovely sort of understanding between the writer and the listener — I’m going to make some stuff up, says the writer, sometimes it will fit and make sense, sometimes it won’t. Okay, says the listener, sure. You do you. I’m just along for the ride. And when it works, when the lyrics and their melody combine with the rest of the instrumentation and with the sonic quality of the whole thing, it’s a neat kind of acrobatics, where the listener just gets it, understands the line in their bones, even when it doesn’t, at face value, make that much sense. In fact, these lyrics are a kind of wonderful nonsense, but I think of them as just more color in the song — more rough surface for the rest of the song to chafe against.

Anyway, this verse muddles along with its fragments and half-ideas, but we know what’s happened to our pair of partiers. They’re together, they’re leaving, they look very fine.

Keep listening.

2:54 Then, instead of our airborne line, that now-expected feint toward a next verse — I saw you breathing / And I saw you staring out in space or I came against (we seem to be shedding lines with each return) — there’s nothing there after “As we were leaving.” Just an ambient ahhh from our singer, and then a healthy amount of noodly twelve-string strumming and picking, with all that Jim Dickinson vibe hanging out behind it. And sometimes over it. I wonder what you picture in your mind as you spend these 30 seconds in this lyric-free environment. In my mind, I’m still with the couple: They’ve left the party and this instrumental interlude soundtracks their next moves, they hail a cab, they’re heading home, or maybe they’re heading off to another, better destination. Whatever it is, it sounds heavenly, doesn’t it? Well, enjoy it while it lasts, because the cowbell is about to arrive.

Go ahead, listen again through to the end.

END That cowbell, huh? I have thought and thought about the cowbell for nearly thirty years. I mean off and on, not all the time — it doesn’t, like, consume my every waking hour. But I do sometimes think about it, even when I’m not listening to the song; I’ll just be minding my business, making my own music or thinking about music and then I’m all of a sudden like, Wow, that cowbell in “Kanga Roo.”

I have tussled lovingly with that cowbell for these thirty years like one does with a rebellious child or a certain preparation of cooked greens or a really difficult whiskey. I first heard “Kanga Roo” on a dubbed cassette copy of Third/Sister Lovers that my uncle sent to me. This was 1991 and he was living in Eugene, Oregon, the home of the University of Oregon. He was immersed in college radio at the time, sending me tapes of all the bands he was discovering. I’d really taken to the copies of #1 Record and Radio City that he’d turned me on to, so he sent me this one, which he dubbed off of a German bootleg — this was before the record had received its Rykodisc reissue. The sides were reversed, as it turned out, so “Kanga Roo” comes along earlier in the track listing than on later releases. My uncle presented it to me with a caveat: This one is weird, it isn’t like the other two, maybe play it when you take a nap. And I took him at his word. I’ve taken countless naps to Big Star’s Third. And you might just be slipping into that liminal space between waking and sleep when the cowbell comes in, just at the top of the final verse. At this point, the song has done most of its work, you’ve been carried away by the fancies of the singer and his sweetheart, this flirty, queen-like lover, and you’re following them along on their odyssey when Jim Dickinson, bless his heart, starts wailing on a cowbell. Out of nowhere. And not only is he wailing on it, but it is, as the parlance goes, the hottest thing in the mix. It’s louder than anything else at that point, or even up to that point. It’s strident and metallic and out of tune with the song, both literally and figuratively. It has a tone, and it’s not in the key of D. It might not even be a cowbell; it might be a pot lid or something. It’s a racket. When I first heard it, I hated it. Why did they have to do that to this song, this beautiful, haunting, sorrowful, ecstatic song? Right when you’re most caught up with it, most captured by its undeniable spell? And then they just…they just shit on it.

But then I listened to it again. And again. And again. Probably by the tenth listen, when I was certain that this somber, odd-shaped record was one of my favorites of all time, I came to love the cowbell. And, reader, trust me when I say that it is the spirit of that cowbell that I aspire to in everything I do, in writing and in music.

Why? I don’t know. There’s something thrilling, something deeply radical, in sabotaging expectations. You thought this was going to be a beautiful, easy song. You thought you were going to be able to nap to this song. Well, think again. It upends everything and, in the process, becomes something truly sublime.

The thing is this: Alex Chilton had laid a challenge on Jim Dickinson. A kind of winky, snide challenge: Do something with this. Produce it. And Jim Dickinson, I believe moved by the attitudes and temperament of his creative partner, decided to accompany the majesty of the track that he’d been handed with some noise. Like I said before, this song is an exercise in the balance between soft and abrasive, light and shadow, vinegar and honey, Steve Buscemi and Timothée Chalamet. This silky cascade of twelve-string guitar has already been abraded by feedback squalls and overloud drums and fuzz bass slides — but the best was yet to come, for here it reaches its apotheosis: the cowbell. And just as our singer, our narrator, vaults us back on to the launch pad with the final verse:

Like Saint Joan

Doing a cool jerk

Oh, I want you

Like a kanga roo

And I’m sorry, but I can’t shed any more light on this verse than you can yourself. We have presumably Joan of Arc dancing a variation on the jerk — the cool jerk, which is also a song by The Capitols from 1966, after the dance of the same name. And then this blithe expression of desire, Oh I want you — like a Kanga Roo — a word that obliterates the cowbell — it’s gone now — it’s just the drums and the Mellotron and Alex oohing over that sloppy twelve-string guitar and the feedback howls and, well, we just get it, don’t we? Aren’t you moved somehow? How would you describe it?

Might I suggest: like a kanga roo.

I love this.

Mindful listening is a lost art in and of itself. Hearing the "ROOM" that these old recordings were made in. It really brings out the human connection aspect of music. It's fun to dance and to have something on in the background to keep your mind occupied, between the hustle and bustle....

But to actually LISTEN and FEEL what went into the craft of transforming a moment in time to something tangible and replayable. Knowing in that instant, as the button on the tape machine clicks and the rest, well the rest is history isn't it?

Thanks Colin! Great track sir!

-Anthony

I think the cowbell comes in as a wake up call. The singer initially sees her across the room and is so taken with her that he can see her breathe. Then I hear the middle, dreamy spacey portion as a fantasy where he imagines going up to her, they leave together, it’s amazing… then the cowbell… no, actually he’s still just at the party, watching her dance. And maybe feels a little foolish, like a kangaroo.