This is an ongoing serialization of an unfinished novel I wrote and Carson illustrated in 2001. New chapters will be published every Friday at 10 a.m. Read Chapter One.

Chapter Two

A wind had picked up and the shutters of Ruthie’s bedroom clattered against the windows and Masha set a glass of hot milk on the bedside table. Ruthie lay quiet in the folds of her blankets as Masha leaned down and kissed her on her forehead. “Sleep well, my sweet,” the maid said and walked softly away from the bedside, out into the hall.

Ruthie stared disquieted at the ceiling after she had left, wondering at the conversation that was undoubtedly ensuing in the room below. What story did the soldier have to tell? What had brought him here so late and in such dire circumstances? She tossed from side to side and kicked at the covers. Suddenly, the wind grew in strength and in a sharp blast, the windows flew open and snow began pouring into the room. Ruthie shot up out of bed and ran to windows, struggling to close them in the gale. Fastening them shut, she caught a glimpse of the light reflected on to the snow of her father’s study. Presently, a silhouetted figure crossed the illuminated stretch of snow, sending Ruthie’s imagination into a flurry of activity. She pressed her cheek to the cold pane in a distant hope that the voices below might rise to her ears, but all she could discern was the hiss of the wind and the occasional petulant lowing of an errant llama. With every moment that passed, her curiosity grew more and more unbridled until she absolutely could bear it no longer—she ran to her bed, slipped into her reindeer skin moccasins and tread softly out her bedroom door into the hall. She tiptoed cautiously across the plush carpeting of the corridor, passing the door to Masha’s chamber from behind which could be heard the whispered hush of prayers being recited in Masha’s soft tenor. Slippering nimbly through the antechambers and the guest rooms of the second floor, she finally reached the great central staircase that wound in a great arc down to the ground floor and, tripping only slightly on a loose swatch of carpet, she walked down the stairs and over to the massive oaken doors that stood between her and the inside of her father’s study. Here, the familiar voice of her father could be easily heard against the whistling of the wind, a breath of strength between the unsteady monologues being spoken by the young soldier. She shuffled slowly to the door and, kneeling down, cocked her ear against the solid wood and listened.

And this is what she heard:

“So it was with no small exuberance that I volunteered to take the voyage,” sounded the quavering voice of the soldier, “considering what I was offered. Imagine: finally I would be set free from this terrible war and allowed to return to my family’s turnip farm, to care for my mother, to see my poor crippled sweetheart again. With this knowledge that had been imparted to me, I immediately felt as if I had been greatly deceived--that we had all been deceived—and that this war in which we all so bravely struggled was ultimately nothing more than a hollow feud and a madman’s game. I well understood the gravity of the undertaking, but, in my anger, felt that no risk was too great in order to bring this whole mess to an end. I signed up in Petersburg and was sent to Arkhangelsk to board a quick little packet barque called The Jouissance. The day we set sail will be etched forever in my head—the lads and me had been two weeks in port and our girls were all standing and waving on the harbor wall, our bookies standing beside them, shaking their fists. God, sir, but we felt as if we were the chosen ones that day. And the wind was high and good and we were two days at sea with a steady nor’easter. I do not pretend to know, sir, the level of your geographical knowledge, but let me tell you that an attempt to cross the Northern Passage is rarely considered to be anything less than suicide. Even a fast clipper in fine wind would be hard pressed to make it through the northern straits without either running into impassable weather or risk being locked in ice come November. It was August, though, and the weather was fine and we knew that if anyone were to succeed in braving the Northern Passage, it was going to be The Jouissance and her crew. We were two weeks at Pyalitsa where we were delivered our precious cargo. Imagine our surprise to see that the thing we were supposed to guard with our lives, with our very souls, and which could potentially bring an end to this whole stupid war, came wrapped in a series of hankies and housed in a little black kit bag, no bigger than your briefcase, sir. Imagine our surprise. Some of the men grew suspicious, feeling as if they were being swindled, that this whole scheme was cooked up so that a few bored officers might have a little sport during wartime away from their clubs and socials. Midshipman Withers, a friend of mine from schooldays, was so convinced that he was being tricked he deserted one night as we were docked there at Pyalitsa. He was discovered three days later in an inn not far from port and was promptly hung from the mainstays as an example. His body hung there for two days, all carrion clawed and rotting, before the officers agreed to cut him down, their intent was so set. After that, it was obvious to everyone that this was no joke.”

“More brandy?” came M. Baumbaum’s voice, filling the space left by the soldier’s sudden silence.

“Yes, please,” said the soldier, “You have been too kind.”

“It is both my pleasure and patriotic duty. But continue—that is, if you are not too tired,” said M. Baumbaum.

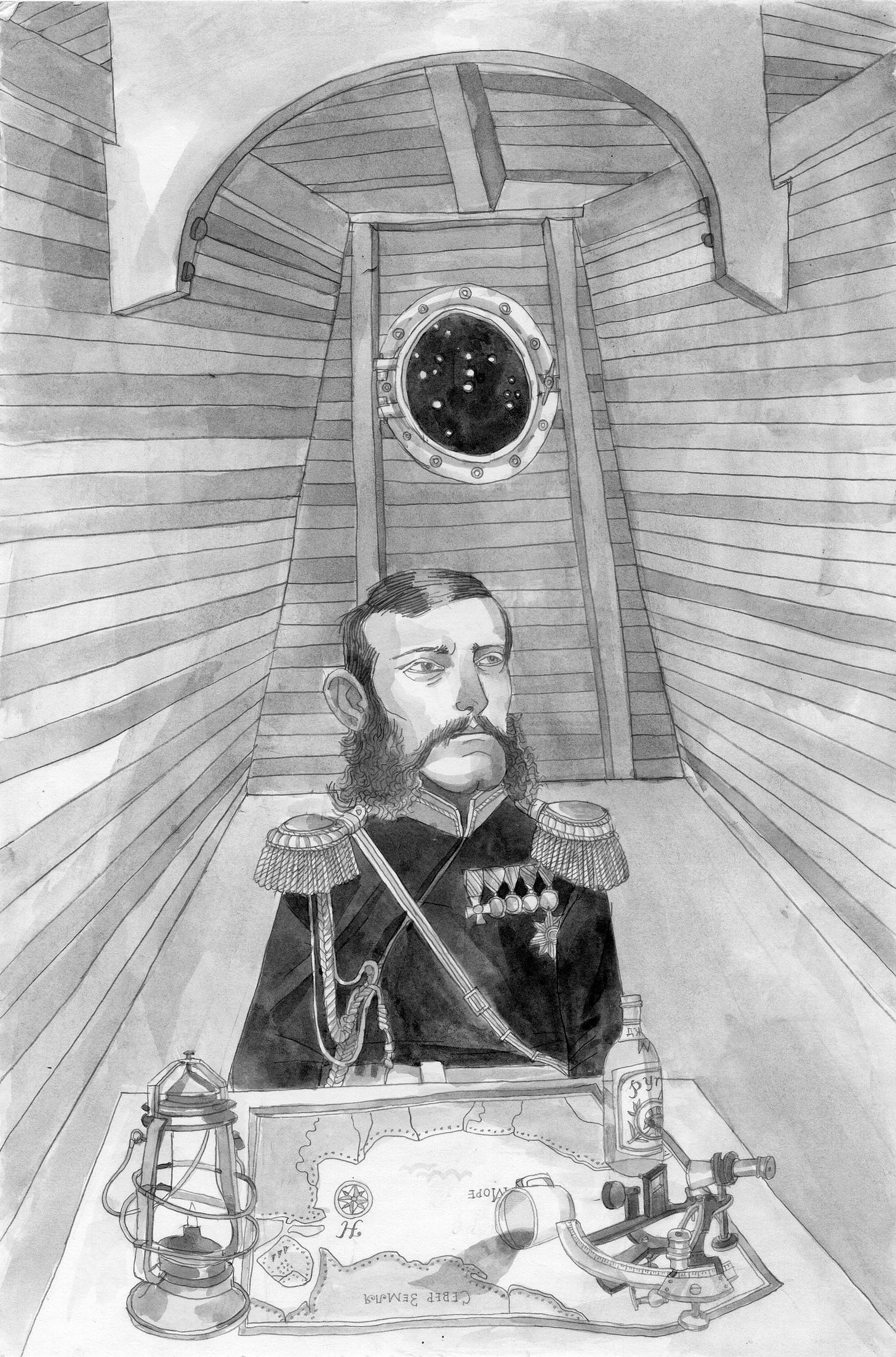

“I fear I may never sleep again, sir.” There was a short pause during which Ruthie imagined the soldier was sipping at his brandy. The soldier then continued: “After Withers’ execution, I was promoted to Midshipman and was supplied with quarters close to the captain. Days at sea are often slack and tedious and I grew very friendly with the captain. His name was Shtiva and he had gone to university in Oxford. His first love was poetry and since I had often read verse during my travails on the turnip farm, we immediately found that we shared a common passion. He took me into his confidences and always weighed my input equally with his seconds in command. One night, after we had been a solid month at sea, I knocked on his door to alert him to the change of watch. He bade me enter and I found him half drunk on spiced rum at his desk, poring over a series of maps and weather charts. Sitting me down, he filled two flagons with rum for he and myself and began softly weeping. ‘What is the matter?’ I asked.

“‘Nothing, aside from the fact that I fear that we all are flying headlong into our icy doom,’ he said. Assuming that he had been reading too much of his beloved romantic poets, I laughed and assured him that he was merely a little in his cups and would forget this all in the morning. He slammed his glass on the table and shouted at me, ‘Damn you, man! Can you not see that we have had nary a breeze since September and are already three weeks behind schedule? If we do not get a decent gust soon, the snow will hit us and we will be locked in ice to our gunnels with nothing but our paltry supply of hardtack to sustain us until the spring thaw. My friend, in two month’s time you will be praying to God that you had never left your precious turnips and gouty lover.’ I calmly looked over the charts and, with what little navigational knowledge I had, could immediately see that what the captain spoke was true. We had been idle in the water for weeks and the air was already growing colder at night and the night was coming sooner every day. ‘Then we will turn back,’ I said. ‘It is not so easy as that,’ the captain said, knocking back his cup of rum, ‘The importance of our voyage is so great that we would not be welcomed back into port. No, I was given the charge of this mission safe in the knowledge that I would either succeed, or die in the trying. And,’ he said, pouring himself yet more rum, ‘It seems as if it will be the latter.’ That night we drank more of his stash of rum than would seem remotely Christian and read aloud our favorite verses and sang the songs of our country until the first mate called morning watch and we fell asleep on the floor in our dungarees.

“Laden with this knowledge, it was difficult for me to continue with my duties, and the next few weeks were fraught with internal turmoil. I went about my normal activities daily, though I lacked my previous zeal. The captain and I stayed apart from one another, almost fearing what the other knew, and when we did see each other on deck, would eye one another with a cold stoicism. We both knew that if we imparted this information to the rest of the crew, mutiny would be certain. No, rather we stayed on our original course and with every day that brought yet more still, quiet air we each felt a shared chill that ran steadily up our spines. When even the slightest movement of wind chanced to move across my cheek, my heart leaped. A mere shudder of the mainsails cracking in the air would send my thoughts into prayer. But nothing could change the fact that we were adrift and heading into arctic waters with nothing but God’s own providence to save us. And at this point, I had very little faith in God’s providence. When the wind finally did pick up, it was too late. That first day when the sails were full and the sun was bright and the crew went about their tasks with renewed vigor I recall looking up at Captain Shtiva on the quarterdeck, looking proudly down on the throng of laborers below him. Unnoticeable to those around me, however, I recognized a pale sadness resting hidden behind those proud steely eyes.

“For the next month, our winds were strong, though with each day the air only grew cooler. The crew members, each of whom was in possession of an unwavering trust in Captain Shtiva, never questioned his leadership though each individually noted a clandestine reservation in each of his barked orders. There seemed to be an ever-present hitch in his voice, like the dulcet tones of a farmer calming his swine before the door to the slaughterhouse. Before we knew it, the air became terrifically brisk and the water untouchably cold. The sun would not rise until late in the afternoon and would set almost immediately following. Ice began to form in the gray pallor of the water, first in small pebbles, which would float innocuously by the hull, then in barrel sized chunks. Soon, the horizon became peppered with the peaks of mammoth icebergs and we were forced to keep several men stationed fore and aft at all times to avoid a fateful collision. The elder shipmates began to grow strongly suspicious of the ship’s course and the safety of her crew and a dangerous unrest quickly began to circulate among the men, though far be it from them to act upon their suspicions considering the fate that befell poor Midshipman Withers. O icy gales! O tempestuous climes! We were well beyond rescue by the time we realized we had gone too far, for too long.

“It was my fate to be on watch that terrible February morning when our fortune to us was revealed. A great fog had consumed the horizon and it was all I could do to strain my eyes to watch for the looming icebergs in the mist. Suddenly, the rhythmic splashing of water against the hull turned violently into the scraping of ice against wood. I ran to the bulwark and squinted my eyes against blue-gray gloom of the morning light only to find my worst fears realized: we had sailed directly into an ice field.

“Immediately, the ship was alive with frantic activity as the horrific grating noise grew deafening in volume. The ice below the ship buckled at its weight and threw great shards of ice over the gunnels while a flurry of snow fell upon the deck, the dusty residue of the ship’s fateful collision. Great peaks of ice, turned upward by the the Jouissance’s hull, grew from the inebriate ocean like mountains rising in holy creation from the plains, unheeding the slow tick of time, their ominous tips rended by the violence of their birth to come crashing down like the spears of savages upon our unsuspecting crew. The planks of the deck became so slick that it was impossible to remain standing against the movement of the ship and the crew was reduced to a bumbling collection of slapstick comedians clawing about, desperately trying to maintain control of the ship. The sound of snapping boards could be heard from deep within the ship’s helm as the Jouissance contorted perceptibly against the unforgiving ice field. I had managed to grab hold of the forestays in the chaos and watched helplessly as the ship was torn asunder. From the quarterdeck, I heard the voice of Captain Shtiva raised against the din, shouting out orders to let slack the sails, to batten the hatches, and to seal off the damaged areas of the bow. He stood resilient, his arms tangled in the ratlines of the rigging to keep himself upright. His barked orders, however, went unheeded as every sailor clung desperately to whatever solid structure they could lay their arms upon as the ship tossed heavily in all directions, a mere toy in the kneading clasp of the ice field. Finally, after what seemed like an eternity of hellish tumult, the ship came to an unhappy rest against the great wall of ice that had grown around the hull. At this point, I recall nothing but silence. Silence and fear.”

The sudden sound of footsteps in the hallway behind her quickly drew Ruthie away from the soldier’s story and, fearful of being caught and severely reprimanded, she scurried behind a large potted fern in the corner of the room. Pyotr, the family’s butler came around the corner pushing a tray cart with a large porcelain cistern atop it. He approached the large door to Baumbaum’s study and, knocking quietly, he allowed himself in. Just as the door closed behind him (it was made of heavy stuff and took a good minute or so to close) Ruthie caught a glance across the concealed room of the bearded soldier sitting in the light of the hearth fire, eyeing the butler suspiciously as he tottered across the rug. Pyotr placed the cistern at the feet of the soldier and, with a nod from Baumbaum, returned to the tray cart and pushed it slowly across the floor and back out into the hall, all before the heavy oaken doors had swung closed. Ruthie watched from behind her leafy cover as Pyotr shuffled down the hall out of view, and, repositioning herself as previously in front of the doors, was left again to the story of the soldier.

Ahhh I often long for the petulant lowing of errant llamas...

I've just published my first novel- a middle grade culinary mystery. One of the elements that my writing partner and I drilled down on, was to ensure that we were "showing" and not "telling" in our sentences...to bring the reader into the experience. Your early book, "How Ruthie Ended the War", succeeds in that, in spades. Chapter Two was exhilarating to read and to also learn the many emotions of the characters. The mysterious visit by the soldier and his vivid tale make me want to read on. It's delightful. Thanks for brainstorming sharing this book.